Folate Supplement Selector

Find Your Best Folate Supplement

Answer these questions to determine which folate supplement most closely matches your health needs. This tool uses information from the article about folic acid, methylfolate, and folinic acid.

When it comes to B‑vitamin supplements, folic acid shows up on pretty much every health‑store shelf. But it isn’t the only player in town. You might have heard about Methylfolate (the active, bio‑available form of folate that the body can use directly), Folinic Acid (also called leucovorin, a reduced form of folate used medically to bypass certain metabolic blocks), and even other nutrients that play similar roles, like Vitamin B12 (a co‑factor that works hand‑in‑hand with folate for red‑blood‑cell formation). Knowing which one to pick can feel confusing, especially if you’re juggling pregnancy plans, heart health, or a chronic condition.

Quick Takeaways

- Folic acid is cheap, stable, and works well for most people when taken at recommended doses.

- Methylfolate is the best choice for anyone with MTHFR gene variants or who needs immediate folate activity.

- Folinic acid is used medically to counteract certain chemotherapy drugs and for rare metabolic disorders.

- Always pair folate‑type supplements with adequate Vitamin B12; low B12 can mask anemia while leaving nerve damage unchecked.

- Dosage matters: more isn’t always better, and high doses can hide B12 deficiency or cause unwanted side effects.

What Is Folic Acid?

Folic Acid (the synthetic form of vitamin B9 used in fortified foods and most over‑the‑counter supplements) is a water‑soluble vitamin essential for DNA synthesis, cell division, and the formation of red blood cells. The body converts folic acid into the active form tetrahydrofolate (THF) through a two‑step enzymatic process that requires the enzyme methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR). Once converted, THF donates single‑carbon units needed for amino‑acid metabolism and for converting homocysteine-a potentially harmful amino acid-into methionine.

Because folic acid is stable at room temperature, food manufacturers fortify breads, cereals, and grain products with it to curb worldwide deficiency rates. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for adults is 400 µg dietary folate equivalents (DFE) daily, and 600‑800 µg DFE for pregnant women.

Alternatives at a Glance

While folic acid does the job for most folks, three alternatives often surface in discussions about optimal folate supplementation:

- Methylfolate (5‑methyltetrahydrofolate, the methylated, biologically active form of folate that bypasses the MTHFR step)

- Folinic Acid (also known as leucovorin, a reduced form of folate that can be directly used in the folate cycle)

- Natural food folate, the mixture of polyglutamated folates found in leafy greens, legumes, and citrus fruits.

Each has a distinct metabolic path, absorption rate, and set of clinical uses. Below we break down the most common reasons people swap one for the other.

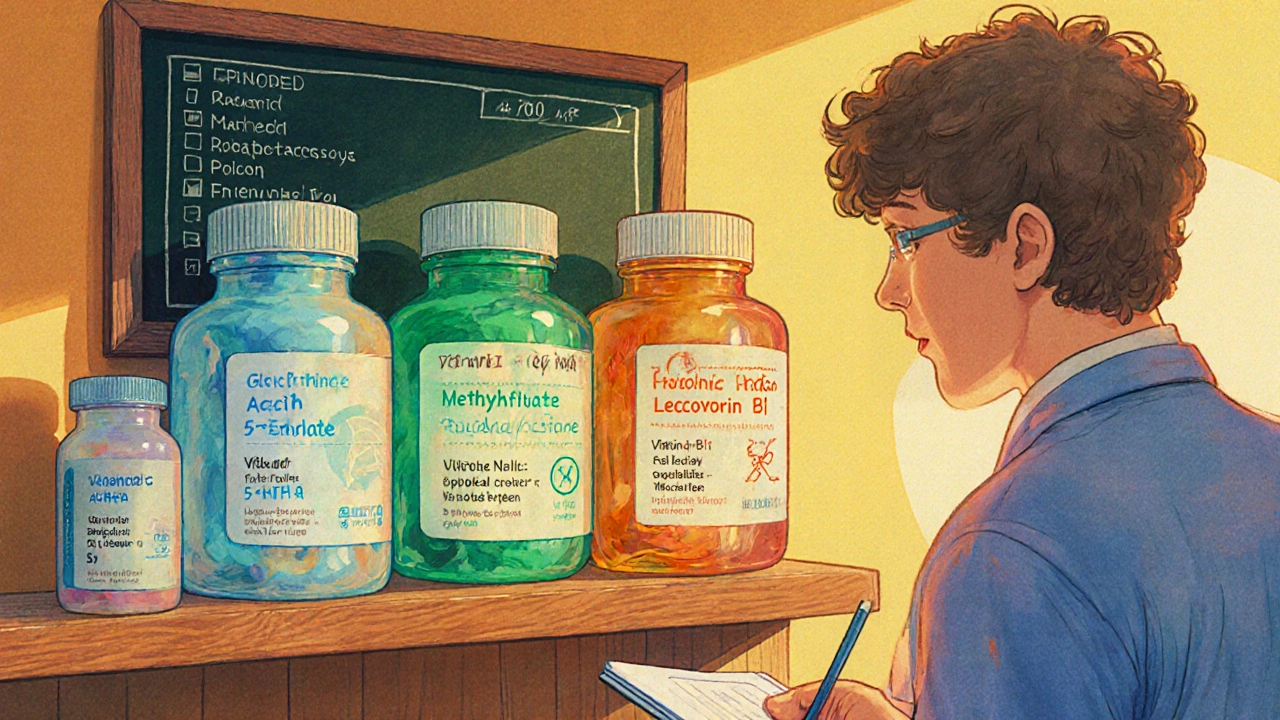

How the Alternatives Differ: A Side‑by‑Side Comparison

| Attribute | Folic Acid | Methylfolate (5‑MTHF) | Folinic Acid (Leucovorin) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Form | Synthetic, oxidized | Natural, methylated, active | Reduced, active (bypasses dihydrofolate reductase) |

| Conversion Needed | Requires MTHFR enzyme | None - ready to use | None - already reduced |

| Typical Dose (µg DFE) | 400‑800 (RDA), up to 1000 for pregnancy | 400‑800, same as folic acid | 250‑500, medical dosing varies |

| Best For | General population, fortified foods | People with MTHFR variants, high homocysteine | Chemotherapy rescue, folate‑deficiency anemia that doesn’t respond to folic acid |

| Safety Profile | Very safe; excess excreted in urine | Similar safety, slight risk of overstimulation in rare cases | Generally safe; high doses can mask B12 deficiency |

| Cost | Low - generic brands under $5 per month | Moderate - $10‑$15 per month | Higher - prescription‑grade, $20‑$30 per month |

The table shows that the big difference lies in how much processing the body has to do. If you have a slow MTHFR enzyme (a common genetic variation), methylfolate can give you the same benefit without the extra metabolic step.

When Folic Acid Is the Right Choice

Most people fall into the "folic acid works fine" bucket. Here’s why you might stick with it:

- Cost‑effectiveness: It’s the cheapest way to meet your daily DFE.

- Proven public‑health outcomes: Countries that fortified grain with folic acid saw a 30‑50% drop in neural‑tube defects (Neural Tube Defects (birth defects of the brain, spine, or spinal cord such as spina bifida)).

- Wide availability: You can find it in multivitamins, prenatal formulas, and even fortified orange juice.

- Stability: Unlike natural food folate, it stays potent through heat and storage.

If you’re a healthy adult with no known genetic issues, the standard 400‑µg dose meets the RDA and supports normal cell growth.

When You Might Prefer Methylfolate

Genetics matter more than you think. About 30‑40% of people carry at least one copy of the MTHFR C677T variant, which reduces the enzyme’s ability to convert folic acid to its active form. Symptoms can include fatigue, elevated homocysteine levels, and mood swings.

Studies from 2023‑2024 show that supplementing directly with methylfolate lowers homocysteine by an average of 15% more than folic acid in this subgroup. If you’ve had a blood test showing high homocysteine, or if you’ve been diagnosed with MTHFR deficiency, methylfolate is the smarter pick.

Pregnant women with MTHFR variants also benefit because methylfolate crosses the placenta more efficiently, ensuring the fetus gets enough folate for neural‑tube closure.

When Folinic Acid (Leucovorin) Is Recommended

Folinic acid isn’t a typical dietary supplement; it’s usually prescribed for specific medical situations:

- Chemotherapy rescue: It’s given after high‑dose methotrexate to protect healthy cells.

- Folate‑deficiency anemia that doesn’t respond to folic acid: Certain rare disorders, like dihydrofolate reductase deficiency, need the reduced form.

- Adjunct therapy for depression: Some clinicians combine it with antidepressants for patients with folate metabolism issues.

Because it’s a prescription‑strength product, you’ll need a doctor’s go‑ahead before you start using it.

Interaction with Vitamin B12 and Other B‑Vitamins

Folate and Vitamin B12 (cobalamin, essential for nerve health and red‑blood‑cell formation) are a dynamic duo. High folic acid intake can hide a B12 deficiency by fixing the anemia but leaving nerve damage unchecked. That’s why you’ll often see prenatal formulas pair folic acid with 2.6 µg of B12.

Other B‑vitamins, especially Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine, a co‑factor in homocysteine metabolism) and Choline (an essential nutrient that supports liver function and brain development), also influence homocysteine levels. A balanced B‑complex can amplify the heart‑protective effects of folate.

Dosage, Safety, and Potential Pitfalls

More folate isn’t always better. Here’s a quick safety checklist:

- Upper Intake Level (UL): The Institute of Medicine sets the UL for folic acid at 1,000 µg DFE for adults. Exceeding it regularly can mask B12 deficiency.

- Pregnancy: The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends 600‑800 µg DFE. Some high‑risk pregnancies (previous child with neural‑tube defect) may need 4,000 µg under doctor supervision.

- Kidney disease: Impaired kidneys clear excess folate slower, so lower doses are advised.

- Medication interactions: Anticonvulsants (e.g., phenytoin) can deplete folate; in such cases, a methylfolate supplement often works better.

For most healthy adults, a daily multivitamin that supplies 400 µg of folic acid hits the sweet spot.

Bottom Line: Pick the Form That Matches Your Body

If you’re a typical adult, stick with standard folic acid. It’s cheap, stable, and backed by decades of public‑health data. If a doctor has flagged a MTHFR variant, high homocysteine, or you’re trying to optimize a pregnancy after a previous neural‑tube defect, switch to methylfolate. And if you’re dealing with a medical condition that requires rapid folate rescue-like post‑methotrexate therapy-your physician will likely prescribe folinic acid.

Whatever you choose, keep an eye on your B12 status and avoid mega‑doses unless a professional tells you otherwise. A balanced B‑vitamin regimen is the easiest way to keep DNA synthesis, heart health, and brain function humming along.

Can I take both folic acid and methylfolate together?

You can, but it usually isn’t necessary. If you’re already getting the active form (methylfolate), the extra folic acid won’t add benefit and may increase the risk of masking a B12 deficiency.

What foods naturally contain folate?

Dark leafy greens (spinach, kale), asparagus, broccoli, beans, lentils, and citrus fruits are top natural sources. A cup of cooked spinach provides about 263 µg DFE.

Is high‑dose folic acid safe during pregnancy?

The recommended upper limit is 1,000 µg DFE. Going above that without medical supervision isn’t advised because it can hide a Vitamin B12 deficiency, which harms fetal nervous‑system development.

How does folate affect heart disease risk?

Adequate folate helps lower homocysteine, an amino acid linked to arterial damage. Meta‑analyses up to 2024 show a modest 10‑15% reduction in heart‑attack risk when homocysteine drops below 10 µmol/L.

Should I test for MTHFR before choosing a supplement?

Testing can be helpful if you have a family history of cardiovascular issues, recurrent pregnancy loss, or unexplained fatigue. Many clinicians order a simple blood test that includes MTHFR genotyping.

Ekeh Lynda

October 24, 2025 AT 12:32The metabolic pathway that turns synthetic folic acid into tetrahydrofolate involves the MTHFR enzyme and can be a bottleneck for many people. When the enzyme activity is reduced the body relies on alternative forms that bypass this step. Methylfolate provides the ready‑to‑use methyl group and therefore sidesteps the conversion requirement. Folinic acid also enters the cycle downstream of dihydrofolate reductase and is useful in specific clinical scenarios. Choosing the right form depends on genetic background, medication interactions and overall B‑vitamin status.

Mary Mundane

November 2, 2025 AT 23:32If you’re not genetically flagged, the cheap folic acid works just fine.

Michelle Capes

November 12, 2025 AT 11:32I get why the whole folate maze can feel overwhelming 😅 many people worry they’re missing something crucial for pregnancy or heart health. The good news is that most labs can check homocysteine and B12 levels before you decide on a supplement. If your numbers are normal you’re probably fine with the standard 400 µg folic acid dose. And remember, the body still needs vitamin B12 to keep nerves happy, so a balanced B‑complex is worth considering.

Dahmir Dennis

November 21, 2025 AT 23:32It’s almost comical how many people swing between miracle‑pill marketing and a blind faith in cheap synthetic nutrients. The notion that a single molecule can solve every pregnancy, cardiovascular, or mood issue is a simplification that borders on dangerous. Folic acid, while inexpensive, was engineered to survive the milling process, not to perfectly mimic the bio‑available forms produced by our own gut flora. Methylfolate, on the other hand, arrived on the market with a price tag that suggests pharmaceutical intent rather than altruistic health promotion. Those who champion it as a universal remedy often ignore the fact that the body already has mechanisms to regulate folate conversion when they are functioning properly. If you have a confirmed MTHFR mutation, bypassing the enzyme makes sense, but for the majority the extra methyl groups are simply wasted. Folinic acid, the so‑called rescue drug, is prescribed in oncology contexts for a reason; it is not a casual substitute for a multivitamin. Yet the supplement aisle is littered with hype, anecdotes, and pseudo‑scientific testimonials that blur the line between evidence and hype. People who indiscriminately stack methylfolate, folinic acid, and high‑dose B12 without lab guidance are essentially gambling with their neurochemistry. The danger lies not in the molecules themselves but in the lack of personalized testing and professional oversight. A proper workup would include homocysteine, serum B12, and, if indicated, a genetic panel for MTHFR variants. Only after those results can you rationally decide whether a 400 µg folic acid tablet suffices or a 1 mg methylfolate capsule is warranted. Otherwise you risk masking a B12 deficiency, causing neuro‑degeneration while your blood count looks deceptively normal. In short, the most responsible choice for the average person is still the low‑cost, well‑studied folic acid combined with a balanced B‑complex. Leave the exotic forms to those with documented medical need, and save your wallet – and your nerves – from unnecessary experimentation.

Jacqueline Galvan

December 1, 2025 AT 11:32From a clinical perspective the decision algorithm begins with a thorough dietary assessment followed by targeted laboratory testing. If homocysteine is elevated while serum B12 remains within reference, methylfolate at 400–800 µg can be introduced safely. For patients with confirmed MTHFR C677T homozygosity, a modest increase to 1 mg may provide additional benefit without exceeding the upper intake level. It is also prudent to monitor renal function, as impaired clearance can alter folate kinetics. Combining the chosen folate form with 2.6 µg of vitamin B12 ensures that the hematologic pathway remains balanced. Regular follow‑up every three months allows for dose adjustment based on emerging biomarkers.

Tammy Watkins

December 10, 2025 AT 23:32Esteemed readers, let us consider the biochemical cascade in a stepwise fashion. The reduction of dihydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate is catalyzed by dihydrofolate reductase, a reaction that is efficiently satisfied by folinic acid in clinical settings where rapid repletion is required. Conversely, the methylation of 5‑methyltetrahydrofolate demands a functional MTHFR enzyme; when this enzymatic activity is compromised, supplementation with 5‑MTHF circumvents the bottleneck. Empirical evidence from randomized controlled trials in 2023 demonstrates a statistically significant reduction in plasma homocysteine when methylfolate is administered to individuals with the C677T polymorphism. Accordingly, the practitioner should individualize therapy based upon genetic and metabolic profiling rather than adhering to a one‑size‑fits‑all regimen. Moreover, vigilance is required to prevent the inadvertent masking of cobalamin deficiency, a phenomenon documented in several cohort studies. Therefore, a synergistic regimen comprising the appropriate folate form, adequate vitamin B12, and supporting nutrients such as pyridoxine and choline constitutes the optimal therapeutic paradigm. Adoption of this precision‑nutrition approach promises to enhance cardiovascular outcomes, support neurodevelopment, and uphold hematologic health.

Dawn Bengel

December 20, 2025 AT 11:32Only a fool would ignore the proven safety of cheap folic acid when our ancestors thrived on natural diets 🇺🇸💪

junior garcia

December 29, 2025 AT 23:32Folates are like the crew on a ship – each one has a role but the captain (B12) keeps everything moving forward.

Dason Avery

January 8, 2026 AT 11:32Think of supplementation as a philosophy of balance – too much of one ingredient can tip the scales, but harmony restores health 😊

Casey Morris

January 17, 2026 AT 23:32While the discourse surrounding folate supplementation is undeniably vibrant, one must not overlook the nuanced pharmacokinetics that govern bioavailability; indeed, the interplay between methylation cycles, renal excretion, and intracellular uptake is a symphony of biochemical precision, and any deviation may precipitate subtle yet clinically meaningful effects, thus warranting a measured, evidence‑based approach.