Quick Takeaways

- Echocardiography offers real‑time insight into clot location, size and hemodynamic impact.

- Transthoracic (TTE) and transesophageal (TEE) approaches complement each other in embolism work‑ups.

- Right‑heart strain on echo is a red flag for pulmonary embolism, while left‑ventricular thrombus points to systemic emboli.

- Doppler imaging quantifies flow disturbances, helping decide anticoagulation or interventional therapy.

- Integrating echo findings with CT or MRI creates a robust, patient‑centred management plan.

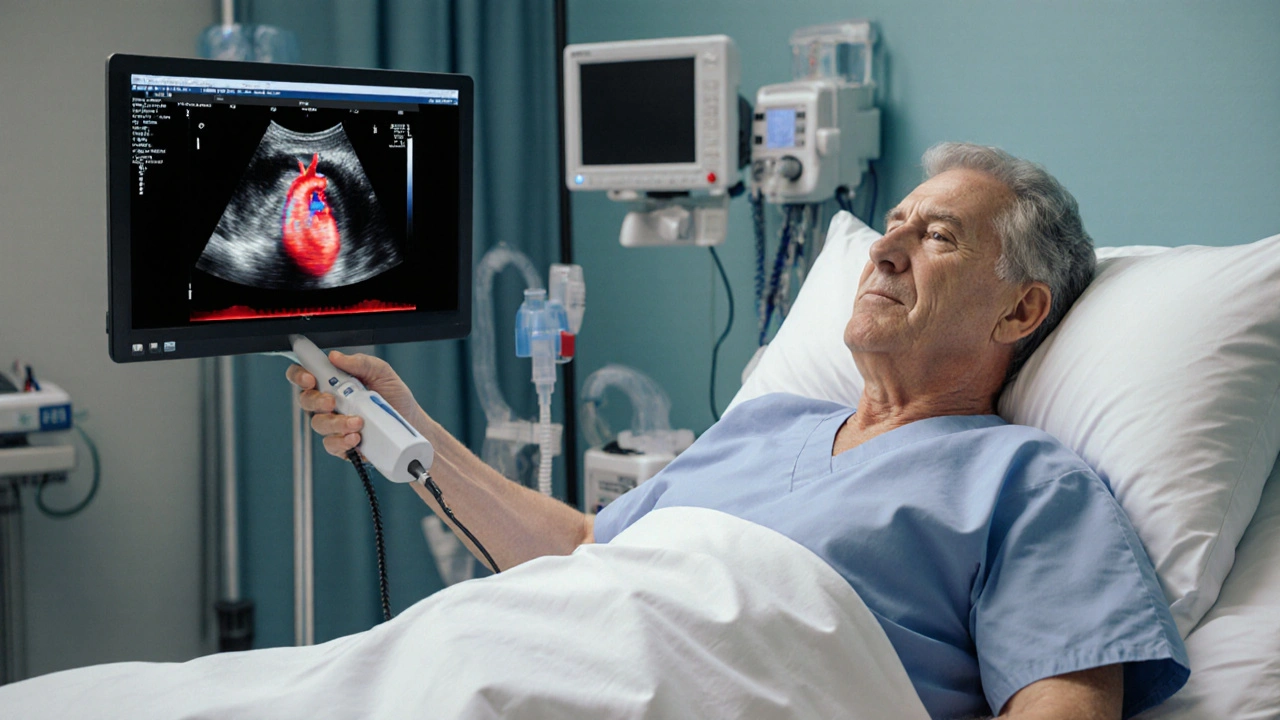

When a clot threatens to block vital blood flow, time is the most critical factor. Echocardiography is a bedside, non‑invasive imaging technique that uses high‑frequency sound waves to visualise the heart’s chambers, valves and surrounding vessels in real time. By turning a handheld probe into a window on the circulatory system, doctors can spot embolic material, gauge its effect on cardiac function, and decide whether to start anticoagulation, thrombolysis, or a surgical procedure. This article walks through why echo has become an indispensable part of embolism diagnosis and how clinicians translate those images into life‑saving actions.

First, let’s set the stage. An Embolism is the occlusion of a blood vessel by material that travelled from another part of the circulatory system, such as a blood clot, fat droplet or air bubble. Emboli can lodge in the lungs (pulmonary embolism), the brain (stroke), the limbs (acute limb ischemia) or any organ that receives arterial blood. While CT pulmonary angiography is the go‑to test for large pulmonary clots, echo steps in when patients are unstable, when radiation exposure must be minimised, or when the clot originates from the heart itself.

Two echo modalities dominate the field: Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is a non‑invasive scan performed through the chest wall, providing a quick overview of heart size, function and any visible masses and Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is an invasive but highly detailed scan where a probe is inserted into the esophagus, offering superior views of the left atrium, atrial appendage and proximal great vessels. Each has strengths and blind spots, and most modern embolism pathways call for both.

Why Echo Beats CT in the Acute Setting

Imagine a patient arriving in the emergency department with severe shortness of breath, tachycardia and low blood pressure. Transporting a critically unstable patient to the CT scanner is risky, and contrast agents may worsen renal function. A bedside echocardiography exam can be completed in under five minutes, revealing right‑ventricular (RV) dilation, interventricular septal flattening, and elevated pulmonary artery pressures-classic signs of acute pulmonary embolism.

Beyond speed, echo provides functional data that static CT images cannot. Doppler imaging is a colour‑flow technique that measures blood velocity, allowing clinicians to detect turbulence caused by a clot and to estimate pressure gradients across valves. A high‑velocity tricuspid regurgitation jet, for example, quantifies RV pressure overload, helping risk‑stratify patients for thrombolytic therapy.

Detecting the Source: Cardiac Thrombus and Atrial Appendage

When a systemic embolus (such as a stroke) is suspected, the heart often hides the culprit. A left‑ventricular mural thrombus, usually seen after a large myocardial infarction, appears as a hyperechoic mass adhering to the endocardial surface. Left ventricular thrombus is an organized clot that forms in the low‑flow area of a damaged ventricle, posing a high risk for embolisation to the brain, kidneys or limbs. Detecting it early directs aggressive anticoagulation and may prompt surgical removal.

In atrial fibrillation patients, the left atrial appendage (LAA) is the most common site for thrombus formation. TEE excels at visualising the LAA due to its proximity to the esophagus. The presence of spontaneous echo contrast-a swirling, smoke‑like appearance-predicts clot formation even before a solid thrombus is visible. This insight often decides whether a patient proceeds to cardioversion or needs a bridge to oral anticoagulants.

Right‑Heart Strain: The Echo Signature of Pulmonary Embolism

RV overload is the hallmark echo finding in acute pulmonary embolism. Specific signs include:

- Dilated RV with a basal diameter >30mm.

- Interventricular septal flattening (the “D‑shaped” left ventricle on short‑axis view).

- Reduced tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) indicating impaired RV contractility.

- Elevated estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure via the tricuspid regurgitation jet.

Combining these parameters into the simplified “RV/left‑ventricular (LV) ratio” helps clinicians categorize patients into low‑, intermediate‑ or high‑risk groups, guiding the urgency of thrombolysis versus anticoagulation alone.

When to Choose TTE vs. TEE: A Practical Comparison

| Feature | Transthoracic (TTE) | Transesophageal (TEE) |

|---|---|---|

| Invasiveness | Non‑invasive, bedside | Invasive, requires sedation |

| Visualization of LAA | Limited | Excellent |

| RV assessment | High quality | Comparable |

| Detection of proximal pulmonary artery clot | Moderate | Superior (via high‑frequency transducer) |

| Patient tolerance | Very good | May cause gag reflex, requires fasting |

In practice, most physicians start with a rapid TTE. If the study shows RV strain but no clear clot, or if a left‑atrial source is suspected, they move to TEE for a definitive look. The decision tree is simple: stability → TTE → if ambiguous or left‑sided source suspected → TEE.

Integrating Echo with Other Imaging Modalities

Echo rarely works in isolation. For pulmonary embolism, a combined approach of CT angiography (to confirm clot location) and echo (to gauge RV impact) yields the most accurate risk stratification. In stroke patients, MRI diffusion‑weighted imaging maps the brain injury while TEE identifies a cardiac source of the embolus. This multi‑modal strategy minimizes unnecessary anticoagulation and improves long‑term outcomes.

Emerging technologies such as three‑dimensional (3D) echo and contrast‑enhanced studies further refine clot detection. Contrast agents-tiny microbubbles injected intravenously-highlight intracardiac chambers and improve the sensitivity for small, mobile thrombi that might be missed on standard gray‑scale imaging.

Practical Tips for Clinicians Performing Echo in Embolism Cases

- Prep the patient quickly. Position the patient supine with the left arm raised to expose the left parasternal window.

- Focus first on the parasternal long‑axis and apical four‑chamber views to assess RV size and function.

- Switch to subcostal view if the patient is intubated; this window often reveals a clear image of the inferior vena cava and right atrium.

- When ruling out LAA thrombus, obtain multiple TEE loops at different angles to avoid missing a small clot.

- Document the TAPSE measurement; values less than 16mm indicate high‑risk RV dysfunction.

- Use colour Doppler to trace any turbulent jets across valves-these may hint at underlying embolic material.

Future Directions: AI‑Assisted Echo Interpretation

Artificial intelligence is already being trained on thousands of echo videos to flag RV dilation, septal flattening, and even subtle LAA thrombus. In a pilot study, an AI algorithm identified left‑ventricular thrombus with 94% sensitivity, outperforming junior cardiologists. As these tools mature, they will serve as a safety net, ensuring that critical embolic findings are not missed during busy shifts.

Until then, mastering the fundamentals of echo remains the cornerstone of embolism care. By visualising the heart in real time, clinicians can pinpoint the clot’s origin, assess its hemodynamic toll, and personalize therapy-all at the bedside.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can echocardiography replace CT for diagnosing pulmonary embolism?

Echo is a rapid, radiation‑free tool that can assess right‑heart strain and suggest a high probability of PE, but it cannot visualise the clot in the pulmonary arteries as clearly as CT. It is best used when CT is unavailable, contraindicated, or when immediate bedside assessment is needed.

When is transesophageal echo preferred over transthoracic?

TEE is preferred when a left‑atrial source (like LAA thrombus) is suspected, when superior resolution of the aortic arch and proximal pulmonary arteries is required, or when the TTE windows are poor due to obesity or mechanical ventilation.

What echo measurement predicts mortality in acute PE?

A TAPSE below 16mm, an RV/LV basal diameter ratio >1, or a systolic pulmonary artery pressure >50mmHg are all strong predictors of adverse outcomes and guide more aggressive therapy.

Is contrast echo safe for patients with kidney disease?

The ultrasound contrast agents used in echo are not nephrotoxic, making contrast‑enhanced studies a safe alternative for patients where iodinated CT contrast is risky.

How often should patients with atrial fibrillation get a TEE to rule out LAA thrombus?

Guidelines recommend a TEE before cardioversion if the patient has been out of therapeutic anticoagulation for more than 48hours, or if there is clinical suspicion of thrombus despite adequate anticoagulation.

Mayra Oto

September 28, 2025 AT 06:03I think echo’s bedside availability really changes how quickly we can start treatment. It gives us a snapshot of cardiac function without moving the patient. For busy ERs, that’s a huge advantage.

S. Davidson

September 30, 2025 AT 13:36While the convenience is undeniable, the diagnostic accuracy still trails CT for locating the actual clot. Echo can show right‑heart strain, but it doesn’t visualize pulmonary artery branches directly. Moreover, the operator dependency introduces variability that many clinicians overlook. If you rely solely on bedside imaging, you risk missing peripheral emboli. The literature consistently shows CT remains the gold standard for definitive diagnosis.

Haley Porter

October 2, 2025 AT 21:09The hemodynamic repercussions of an embolic event are best interrogated via Doppler-derived velocity profiles. When you assess tricuspid regurgitant jet velocity, you gain insight into pulmonary artery pressure surges. This physiologic data, coupled with morphological RV dilation, creates a robust risk stratification schema. Echo thus serves as a functional adjunct rather than a purely anatomic modality. Integrating these parameters optimizes therapeutic decisions.

Samantha Kolkowski

October 5, 2025 AT 04:43yeah, i totally get that echo can be super helpful, especially when you cant move a patient easily. its just that sometimes the windows are not so great if the pt is obese or mechanical vent. you might end up missin a small thrombus and thats a problem. still, its a good first step in most cases.

Nick Ham

October 7, 2025 AT 12:16Echo beats CT for bedside speed.

Jennifer Grant

October 9, 2025 AT 19:49When I first stood at the bedside with a handheld probe, I felt like a modern mariner charting unseen currents beneath the surface of a stormy sea. The echo machine, humming softly, revealed the silent drama of a right‑ventricular wall flailing under sudden pressure, a mechanical sigh of distress that no CT slice could convey in real time. Each frame, each Doppler sweep, painted a narrative of hemodynamic compromise that beckoned immediate intervention, reminding us that medicine is as much about timing as it is about technique. The ability to watch the heart’s chambers dance – or convulse – in response to an embolus grants clinicians a privileged glimpse into the body’s rapid compensatory choreography.

Yet, the technology is not without its quirks; acoustic windows can be mischievous, especially in patients with extensive barotrauma or morbid obesity, causing the image to dance in and out of focus like a flickering candle. In such moments, a transesophageal approach acts as a trusty lantern, guiding the eye past the obstructive ribs to the lurking left atrial appendage, where thrombi may hide like furtive shadows.

Clinical guidelines now weave echo findings into decision trees, pairing RV/LV ratio thresholds with anticoagulation protocols, and assigning meaning to a TAPSE value below 16 mm as a herald of poor prognosis. The literature, replete with meta‑analyses, confirms that a bedside echo that shows RV overload can stratify patients into high‑risk categories even before a CT angiogram confirms clot location.

Moreover, the portable nature of modern machines democratizes advanced cardiac imaging, allowing physicians in remote or resource‑limited settings to detect life‑threatening emboli without waiting for an MRI suite. This democratization, however, carries the responsibility of training – novice operators must learn to distinguish reverberation artefacts from true masses, lest they over‑call a stray echo as a dreaded thrombus.

In practice, I have seen echo alter the course of care dramatically: a patient arriving in shock, a swirling “smoke” in the left atrium, prompting immediate anticoagulation and averting a catastrophic stroke. Conversely, I have witnessed a false‑negative TTE where the RV appeared normal, only for a later CT to reveal a massive saddle embolus, underscoring the need for multimodal confirmation.

The future looms bright as AI begins to patrol echo loops, flagging RV dilation and subtle LAA thrombi with uncanny precision, acting as a safety net for fatigued clinicians. Until those algorithms become ubiquitous, the art of echo rests on the shoulders of observant, skilled hands willing to interpret both the obvious and the nuanced. In the end, echo is not just a snapshot; it is a living dialogue between the heart and the physician, a conversation that can mean the difference between life and death in the narrow window of an embolic crisis.

Kenneth Mendez

October 12, 2025 AT 03:23They don’t want you to know that bedside echo can replace a bunch of pricey scans. The big med companies push CT because it lines their pockets, not because it’s always better. When you look at the data, you see echo catching right‑heart strain faster than any lab. Stay skeptical, question the hype, and trust the real‑time view.

Gabe Crisp

October 14, 2025 AT 10:56Ethical practice demands we use the least invasive, most informative tool available. Echo respects patient autonomy by avoiding radiation. It also aligns with prudence, reserving CT for cases where anatomical detail is absolutely required.

Paul Bedrule

October 16, 2025 AT 18:29The ontological substrate of echocardiographic imaging offers a phenomenological window into thrombotic ontogenesis. By quantifying spectral Doppler shifts, we infer the kinetic energy gradients that herald embolic migration. Such semiotic analysis transcends mere morphology, embedding causal inferences within the cardiac silhouette.

yash Soni

October 19, 2025 AT 02:03Oh great, another echo tutorial. Because we definitely needed more of those.

Emily Jozefowicz

October 21, 2025 AT 09:36Wow, look at this dazzling display of cardiac ultrasound-so vivid it practically paints a picture in the mind! Yet, if you’ve read beyond the headline, you’ll see the nuance of when to trust echo over a scan. The article does a stellar job, but remember, every tool has its sparkle and its shade.

Franklin Romanowski

October 23, 2025 AT 17:09I really appreciate how the piece walks through both the technical and compassionate sides of patient care. Knowing when a quick bedside echo can spare a patient from a risky transport is invaluable. The clear step‑by‑step approach makes it easy to remember during a hectic shift. It also reminds us that every diagnostic choice hinges on the individual's situation. Thanks for the thoughtful synthesis!

Brett Coombs

October 26, 2025 AT 00:43Everyone jumps on the echo bandwagon, but have you considered the bias in the literature? Mainstream cardiology loves its shiny new toys, yet ignores the limitations of probe placement in certain populations. I’d love to see a counter‑study that actually challenges the hype.

John Hoffmann

October 28, 2025 AT 07:16While simplifying terminology is helpful, the article occasionally misuses “D‑shaped” to describe septal flattening-technically it refers to the short‑axis view, not a diagnostic sign itself. Likewise, “right‑ventricular strain” should be qualified with quantitative parameters such as RV/LV ratio. Consistency in nomenclature would improve clarity.

Shane matthews

October 30, 2025 AT 14:49Nice summary of echo use in embolism cases great read thanks

Rushikesh Mhetre

November 1, 2025 AT 22:23Fantastic article! Echo truly shines in emergencies-quick, portable, and informative!!! The step‑wise algorithm you outlined is super practical for busy clinicians!!! Keep up the great work, and consider adding a quick‑reference table for Doppler thresholds!!!

Sharath Babu Srinivas

November 4, 2025 AT 05:56Great insights! 😊 The way you highlighted RV strain and LAA thrombus is spot‑on. Echo really bridges the gap between rapid assessment and detailed evaluation. Looking forward to more pieces like this! 👍

Halid A.

November 6, 2025 AT 13:29The presentation is thorough and aligns well with current guidelines. It offers clear recommendations for when to transition from TTE to TEE, facilitating decision‑making in acute settings. Incorporating a brief checklist could further aid clinicians under pressure.

Brandon Burt

November 8, 2025 AT 21:03Honestly, the article feels a bit like a rehash of stuff I've seen a thousand times. Sure, echo's handy, but the writers could've dug deeper into emerging AI tools and their real‑world pitfalls. Also, the table formatting is clunky-hard to read on mobile. Overall, decent but not groundbreaking.