Safe Medication Disposal Guide

This tool helps you determine the safest way to dispose of expired medications based on FDA guidelines. Follow these steps to ensure safe disposal that protects people, pets, and the environment.

Step 1: Check Your Location

Step 2: Check Medication Type

Step 3: Additional Considerations

Recommended Disposal Method

Step-by-Step Instructions

Important Safety Notes

Keeping old pills in your medicine cabinet isn’t just messy-it’s dangerous. Every year, millions of unused or expired medications end up in homes, where kids, pets, or visitors might accidentally swallow them. Worse, some get flushed down the toilet or tossed in the trash, polluting water supplies and fueling the opioid crisis. The FDA has clear, science-backed rules for what to do with expired meds-and most people are doing it wrong.

Why Proper Disposal Matters

In 2022, U.S. pharmacies dispensed over 5.8 billion prescriptions. About 15-20% of those went unused. That’s hundreds of millions of pills sitting in drawers, bathrooms, and kitchens. The CDC reported over 70,000 drug overdose deaths that same year, with prescription opioids involved in nearly 13,500 of them. A big reason? Easy access to leftover meds at home. The FDA, EPA, and DEA all agree: the safest way to get rid of unused medications is through drug take-back programs. These programs prevent misuse, protect the environment, and save lives. Yet, a 2024 Consumer Reports survey found that 78% of households still try to dispose of meds on their own-often incorrectly.The FDA’s Three-Step Disposal System

The FDA doesn’t just give vague advice. They’ve built a clear, tiered system based on risk and availability. Here’s how it works:- Use a take-back location-this is your #1 choice for almost every medication.

- Use a mail-back envelope-if no drop-off site is nearby.

- Dispose at home-only if the first two aren’t possible, and only for meds NOT on the Flush List.

Take-Back Locations: Your Best Option

As of January 2025, there are over 14,352 DEA-authorized collection sites across the U.S.-mostly at pharmacies like CVS, Walgreens, Walmart, and local hospitals. These are secure kiosks where you can drop off pills, patches, liquids, and even needles (in approved containers). You don’t need a prescription or ID. Just bring the meds in their original bottles (no need to remove labels yet). The DEA collects these twice a year during National Take-Back Days-April 26 and October 25, 2025-but permanent sites are open year-round. Why is this the gold standard? Because take-back programs have a 99.8% proper disposal rate. That means nearly every pill collected is destroyed safely, with zero chance of being stolen or leaking into waterways.Mail-Back Envelopes: A Reliable Alternative

If you live in a rural area with no nearby drop-off site, mail-back envelopes are your next best bet. Companies like DisposeRx and Sharps Compliance offer pre-paid, FDA-compliant envelopes that let you send meds back to licensed disposal facilities. These envelopes cost between $2.15 and $4.75 each, but many insurers and VA programs provide them for free. Express Scripts reported 94.2% user satisfaction among 287,000 participants in 2024. Military families using VA-provided mailers had an 89.2% compliance rate-far higher than those relying on home disposal. Important: Only use FDA-approved vendors. Generic envelopes from Amazon or pharmacies without clear labeling may not meet safety standards.Home Disposal: What to Do When Nothing Else Works

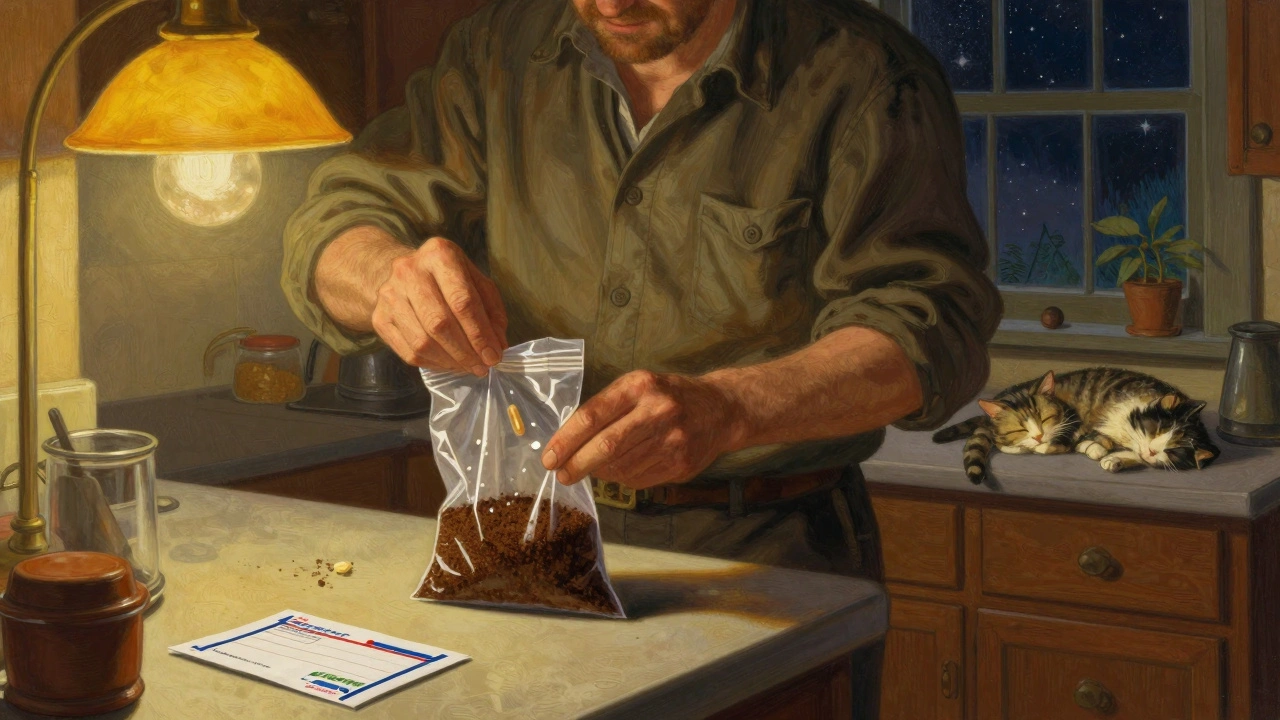

If you can’t access a take-back site or mail-back service, you’re allowed to throw meds in the trash-but only if they’re not on the FDA Flush List. Here’s the exact 5-step process:- Remove personal info-Use a permanent marker or alcohol swab to completely black out your name, prescription number, and pharmacy details on the bottle.

- Mix with unpalatable stuff-Combine pills or liquids with coffee grounds, cat litter, or dirt in a 1:1 ratio. This makes them unappealing and unusable. Coffee grounds are preferred by 78% of users because they mask smell and texture.

- Seal in a container-Put the mixture in a plastic bag or container with walls at least 0.5mm thick. Ziplock bags work. Don’t use paper or thin plastic.

- Put it in the trash-Not the recycling bin. Not the compost. The regular garbage.

- Recycle the empty bottle-Once it’s completely de-identified, remove the label and toss it in recycling.

The FDA Flush List: When Flushing Is Allowed

There are only 13 medications that the FDA says you can flush if no other option is available. These are all high-risk drugs that can cause immediate harm if accidentally ingested-especially by children or pets. The current Flush List (updated October 2024) includes:- Fentanyl patches

- Oxycodone (OxyContin, Percocet)

- Hydrocodone (Vicodin)

- Buprenorphine (Suboxone)

- Hydromorphone

- Morphine

- Meperidine

- Tapentadol

- Alprazolam

- Clopidogrel

- Remifentanil

- Levorphanol

- Tramadol

What NOT to Do

Many people think flushing or tossing meds is harmless. Here’s what you must avoid:- Never flush non-Flush List meds-Even common painkillers like ibuprofen or acetaminophen can contaminate water. The EPA prohibits this for households and pharmacies alike.

- Never pour liquids down the sink-Liquid meds must be mixed with absorbent material first.

- Never throw pills in the recycling-They’re not paper or plastic. They’re hazardous waste.

- Never leave bottles with labels intact-Your personal info can be used for identity theft.

What About Pills in Blister Packs?

You don’t need to remove pills from blister packs. Just leave them in, mix the whole pack with coffee grounds or cat litter, seal it, and throw it away. Removing pills increases risk of accidental exposure and isn’t required.Environmental Impact: The Hidden Cost

Flushing medications contributes to trace amounts of pharmaceuticals in water systems. The USGS found that flushing accounts for just 0.0001% of total pharmaceutical contamination-but it’s still pollution. The EPA says even tiny amounts can affect aquatic life, and the long-term effects aren’t fully known. That’s why the EPA’s official stance is stronger than the FDA’s: “Flushing should never be the first choice for any medication, even those on the Flush List.” The good news? Take-back programs eliminate this risk entirely. And with the EPA’s new $37.5 million grant program announced in February 2025, more communities will soon have access to drop-off sites.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The system is getting better:- The DEA plans to expand take-back sites to 20,000 locations by the end of 2025.

- Walmart now has take-back kiosks in all 4,700 of its U.S. pharmacies.

- CVS has invested $15 million in mail-back programs serving 10 million customers yearly.

- The FDA aims for 90% of Americans to use take-back programs by 2030-up from just 35.7% in 2024.

What If You’re in a Rural Area?

If you live more than 25 miles from a drop-off site, you’re not alone. The National Rural Health Association found that 31.4% of rural residents have no nearby take-back option. Your best move? Sign up for a mail-back envelope through your pharmacy, insurer, or VA. Many are free. If that’s not possible, follow the home disposal steps exactly-mix, seal, trash, recycle the bottle.How to Find a Take-Back Location Near You

The easiest way is to visit the DEA’s website and use their Drug Disposal Locator. You can also:- Call your local pharmacy-most now have kiosks.

- Check with your city or county health department.

- Ask your doctor or hospital-they often host collection events.

Final Checklist: Safe Disposal in 5 Steps

Before you toss that old bottle, ask yourself:- Is this on the FDA Flush List? If yes, and no take-back is nearby, flush it.

- If not, find a take-back location first.

- If none exists, use a mail-back envelope.

- If neither is possible, remove labels, mix with coffee grounds or cat litter, seal in a thick plastic bag, and throw it in the trash.

- Recycle the empty bottle after scrubbing off all personal info.

Can I flush any expired medication if I don’t have a take-back option?

No-only medications on the FDA’s official Flush List (13 specific drugs, mostly strong opioids) can be flushed, and only if no take-back site is within 15 miles or 30 minutes. Flushing other meds contaminates water supplies and violates EPA guidelines. Always check the latest FDA list before flushing.

What if I don’t know if a medication is on the Flush List?

Check the prescription label or ask your pharmacist. If you’re unsure, don’t flush it. Use the home disposal method instead: mix with coffee grounds or cat litter, seal in a plastic bag, and throw it in the trash. Pharmacies are required to provide this info under FDA rules.

Can I throw pills in the recycling bin with the bottle?

Never. Pills and liquid meds are hazardous waste and must never go in recycling. Even empty bottles should only be recycled after you’ve completely removed or blacked out all personal information. Otherwise, you risk identity theft and environmental contamination.

Are mail-back envelopes really safe and legal?

Yes-if they’re from an FDA-approved vendor like DisposeRx or Sharps Compliance. These envelopes meet USPS and DEA standards for secure pharmaceutical transport. They’re used by the VA, Medicare plans, and major insurers. Avoid generic envelopes sold online without clear compliance labeling.

Do I need to remove pills from blister packs before disposal?

No. The FDA says you can leave pills in their blister packs. Just place the entire pack into the mixture of coffee grounds or cat litter, seal it in a plastic bag, and throw it in the trash. Removing pills increases the risk of accidental exposure and isn’t necessary.

What about liquid medications like cough syrup?

Liquid meds must be mixed with an absorbent material like cat litter, coffee grounds, or dirt before disposal. Pour the liquid into a container with the absorbent, stir until it’s soaked up, seal it in a plastic bag, and throw it in the trash. Never pour liquids down the drain or toilet.

Can I dispose of expired medications at my doctor’s office?

Most doctor’s offices cannot legally accept medications for disposal due to DEA and EPA regulations. They’re not authorized collectors. Your best bet is a pharmacy take-back kiosk or mail-back program. Some hospitals or community health centers may host collection events-call ahead to ask.

Mia Kingsley

December 12, 2025 AT 05:02Katherine Liu-Bevan

December 13, 2025 AT 06:43Courtney Blake

December 13, 2025 AT 12:25Kristi Pope

December 14, 2025 AT 04:04Regan Mears

December 14, 2025 AT 07:49Neelam Kumari

December 15, 2025 AT 05:07Queenie Chan

December 15, 2025 AT 22:59Stephanie Maillet

December 16, 2025 AT 15:24David Palmer

December 16, 2025 AT 15:36Vivian Amadi

December 18, 2025 AT 05:55Jimmy Kärnfeldt

December 18, 2025 AT 16:13Ariel Nichole

December 18, 2025 AT 18:31john damon

December 19, 2025 AT 15:59matthew dendle

December 20, 2025 AT 01:45Jim Irish

December 20, 2025 AT 19:17